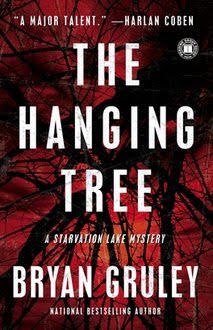

Harlan Coben calls Bryan Gruley “a major talent” and Publishers Weekly proclaimed that he will remind readers of Dennis Lehane. Do you need any more reason to read his latest gripping mystery? To whet your appetite, I am giving you an interview with Gruley.

Tell us about the process of plotting a mystery novel. Do you have the story mapped out before you sit down to write, or do you discover it along with your characters?

So far, I’m not much of an advance plotter. I know where the story begins and I have a vague idea of how it ends. Then I start writing and, yes, I discover the story along with my characters. As I go, I jot notes to myself about story arcs I need to follow through on and loose ends I have to tie up, and these become a sort of rough, moving outline for what’s to come in the next few scenes.

How is writing a sequel different from writing a debut novel? Does your writing process change at all?

Writing my first novel was hard because I had no idea how to go about writing a novel. Writing the sequel was hard because I had no idea how to go about writing a sequel.

I don’t mean to be glib. In a sequel, you have to be mindful both of readers who have not read your previous book and readers who have. You have to give the former enough backstory to appreciate the setting and characters without giving so much that you either bore repeat readers or reveal so much of the first book that new readers won’t go back and give it a try.

At least for me, another challenge on the sequel was quieting the echoes of reviewers, bloggers, readers, and others who had opined about my writing. Writing my debut, all I had to worry about were my own instincts and the suggestions of the few friends who read the manuscript. This time around, it was impossible at times not to recall the critics, professional or not, who’d complained about the hockey or the dialogue or the prologue or the way my hair was done in the author photo. It made for some second-guessing, but I tried to remind myself what my friend, the novelist John Galligan, told me: Write what’s in your heart.

When you first conceived of this series, how did you decide which point of view to tell the story from? Did you ever consider using a character other than Gus to narrate, or telling the story from a third-person perspective?

In truth, I didn’t conceive of a series; I just wrote one story, Starvation Lake, and my friends at Touchstone told me it would be a series.

I never gave serious thought to telling my story in anything but the first person. It just felt natural, and it really helped me to get to know at least one character, Augustus Carpenter. I sometimes feel envious reading stories told in third-person omniscient, because the narrator can honestly know things that the main character cannot know. I do not have that luxury with Gus, of course, but for now at least, I feel that it’s his voice more than anything that connects with certain readers.

While you don’t write from a female perspective, there are several strong female characters at the heart of The Hanging Tree (particularly Gracie, Felicia, Darlene, and Michele). Do any of the women in your life inform your female characters?

Absolutely. While none of these fictional characters are modeled on particular women in my life, I assume that virtually every girl or woman I’ve ever known has influenced the way in which I’ve drawn them—and the way Gus perceives them. The latter is most important because it tells us as much about Gus as it does about them.

Felicia and Laird Haskell put a lot of pressure on Taylor. Throughout the novel, Gus describes the dashed dreams of parents who believed that their sons were bound for the NHL. Do you think that this kind of pressure from parents is more intense in small towns like Starvation Lake?

I doubt it. Remember that the Haskells originally hail from the Detroit suburbs. The pressure there—and in Chicago, Toronto, Minneapolis, Montreal, Boston, and other hockey towns—can be intense. The best parents understand that the odds of their kid playing pro hockey are infinitesimal. They instead encourage a love of the game that the kid can embrace for the rest of his or her life.

Philo’s belief in the potential of the Web to change journalism is pivotal to the story. You have experienced the changes affecting journalism firsthand. Do you think that the essential role of reports has shifted in the information age, or is their basic purpose and process the same? Are you optimistic about the future for newspapers in America?

The reporter’s mission is as ever: tell people things they didn’t know five seconds ago, and tell them stories that make them think, laugh, debate, cry, act. Today, a young reporter is likely to be as adept with a video camera as she is with a pen and notebook, and he’s likely to deliver information in shorter, faster blasts than before. But the essentials remain unchanged: What’s new? What’s interesting? How does it affect me and my world?

I’m not optimistic about the future for print newspapers, per se, because the business model is broken beyond repair. But the demand for news, compelling tales, and insightful analysis in an increasingly connected, increasingly complex world is greater than ever. The challenge is finding ways to deliver that material in ways that people will actually pay for.

Tell us about your plans for Gus and Starvation Lake. Will the series continue? Any thoughts on how many books there might be?

At least one more, according to the folks at Touchstone. I can envision more beyond that, because I enjoy the characters so much. I’m dying to know what will happen to Soupy and Bea and Darlene and the River Rats. The only way to find out is to sit down and write it.